Growing Fruit Trees

There's a fruit tree for every space and they aren't difficult to grow. That's the word in all enthusiastic garden manuals. Sure, they aren't difficult to grow, but you have to follow some rules to achieve success!

The tree has to suit the climate, the position in the garden and, most importantly, the soil. Healthy soil is imperative for good tree growth and fruit. There's lots of information pages on soil on the SGA website that will help you get the ground right before you plant.

There are other fruit tree types besides citrus and deciduous, but these are the most popular types of fruit trees planted in the southern states.

People in cooler regions are having success with some tropical fruits too, such as avocados in Melbourne. The rules are the same, except these plants will not tolerate frosts, especially when young. They need to be placed in a warm sunny spot with plenty of summer water.

Citrus

Citrus, which includes lemons, oranges, grapefruit, mandarins, limes and cumquats, do best in warm and mild climate zones. Trees will tolerate some mild frost though.

They like a sunny position. Make sure they get plenty of winter sunshine too by facing them north. Protect them from wind (and they don't tolerate salt-laden wind).

They don't like heavy clay soil, doing best in sandy or loam soils. Heavy soils that don't drain well can lead to root rot problems.

Citrus trees generally have shallow rooting systems, so can dry out rapidly in summer. Mulching to prevent summer soil water loss is a necessity.

Being shallow rooted means roots can be damaged easily by cultivation, so avoid cultivating around them, especially at the dripline (the perimeter of the canopy) as this is where most of the feeder roots are.

They don't need pruning usually. If growth gets overcrowded some thinning of inward growing stems will open it up. Oranges and grapefruit don't tolerate severe thinning or pruning. Lemons can be cut back quite well to keep them at a manageable height. Lemons can be espaliered.

Sappy water shoots often grow at the base of lemon and grapefruit trees and these should be cut off. If the tree is a grafted variety, all shoots below the graft need to be removed.

Citrus respond to fertiliser (composted animal manure is ideal) best at the end of winter and then again in late summer. Apply to dripline.

Fruit drop is a common problem and is often due to irregular or uneven watering. Lack of fertiliser or too much can also cause this problem.

Deciduous Fruit Trees

These trees produce fruit in summer, and they lose their leaves and are dormant over winter. Includes apples, pears, plums, peaches, and nectarines.

Because they are dormant in winter they can be grown in areas that have cold winters and severe frosts (late frosts can destroy flower and leaf buds though).

Deciduous fruit trees are often sold as bare-rooted plants during winter, and this is generally the best time to buy and plant. It is possible to plant at any time, but careful watering is essential.

They need plenty of sunshine and will grow in a variety of soil types, although most don't tolerate very heavy soil.

If planting during winter, don't add fertiliser until late winter, as the plant is dormant and can't use the nutrients. Most fruit trees will require yearly applications of fertiliser, applied in late winter. (composted animal manure is ideal)

Most deciduous trees are pruned to a vase shape (although many can be espaliered) and are pruned in winter. Pruning is usually hard for the first few years to develop a good shape. Later pruning is to remove dead wood, ingrowing branches, thin overcrowding branches, or to cut back leaders or main limbs.

Each kind of tree has its own habit of growth, and some require two trees (a male and female) in order to produce fruit. Get more information on specific trees from your garden centre or from gardening books (the local library is a brilliant resource).

Fruit trees can be susceptible to a wide range of pests and diseases. For more information on pest and disease control, refer to What Garden Pest or Disease is That?, by Judy McMaugh, (published by New Holland). Remember though, keep the tree healthy and that's half the battle.

Reference: Yates Garden Guide, published by Harper Collins

Roses

An abridged version of an article supplied to SGA by Barry W. Johnson of Hearts Content Horticultural Services.

Roses are an internationally renowned garden mainstay and form a huge part of the commercial horticultural world. As I also have a long history as a rosarian, my brief is to emphasise that sustainable gardening principles can be applied to rose culture as much as to any other genera or cultivars.

Aren't Roses High Maintenance?

No, not necessarily. If you intend to grow roses to win prizes at a rose show, you may have to treat them like a Harley Davidson. But if you just want to grow them for a pleasant garden display, you will find them quite hardy subjects.

As a general rule, the modern cultivars such as the hybrid teas, miniatures etc. may require a little more attention to detail to produce optimum results, but most of the other classes will still perform adequately by the employment of sustainable garden practices. In actual fact, there has been a worldwide trend by rose breeders and growers to produce modern, disease resistant, floriferous, and easy-care shrub roses.

Roses and Friends

In addition, many of the Species and Old Garden Roses will tough it out quite well with our beloved natives so long as they can get off to a good start and they are not thrown into terra too-firma. Good soil preparation is really a vital ingredient of planting out any plant, roses being no exception.

Any companion plants to be included with roses should have two basic characteristics: a deep, non-fibrous root system; and a non-blanketing foliage canopy. Companion plants having both these traits should allow the rose to establish properly and live harmoniously with its neighbours. The problems associated with having to compete in close proximity to another plant's overly voracious root system is obvious, but the reason roses do not like being covered by blanketing leaves is heavy over-shading. This robs the rose of this sunlight which in turn can cause poor vigour and die-back.

A certain amount of investigation and discrimination should be employed when selecting companion plants you are trying to intermingle with roses. Roses require at least 50% of sunlight per day so I'm sure any rose is going to have trouble living under the canopy of a large dense canopied tree like Melaleuca linariifolia for example, not to mention the hunger and thirst of its root system.

I also advise that, if possible, the planting out of the roses prior to, or at the same time as your larger companion shrubs and trees to enable the rose to get a good start. Obviously, if you intend to plant roses in proximity to established companion plants you will have to rejuvenate the soil in the planting zone and get them off to a good start.

When The Going Gets Tough

If your preference leans toward an arid or extremely low maintenance garden, then Species roses and their near relatives would be the obvious choice. Although there are no native Australian roses, species roses and their near-relatives originate from a wide range of habits spanning from the far north of the northern hemisphere to Africa & Middle East, eg. Rosa acicularis (Arctic Rose) and Rosa foetida persiana (Persian Yellow Rose). True species and their near-relatives like the Gallicas, and Spinossissimas are a good starting point in tough rose selection. Note though that R. rugosa is an environmental weed.

Some suggested species to try would be:- R. foetida, R. banksiae lutea (Banksia Rose, pictured left), R. brunonii, R. officinalis, R. complicata, R. Tuscany Superb, R. rubifolia, R. hugonis, R. moschata, R. moyesii 'Geranium', R. mutabilis, R. nitida, R. 'Irish Rich Marbled', R. roxburghii, R. scabrosa, R. 'Blanc Double De Colbert', R. sweginsowii. Add to these many of the Damasks, Albas, Centifolias, Mosses, and Portlands, and you have quite a range to choose from.

In addition to these there are a number of shrub roses that are tough and reliable, such as, 'Angela', 'Fruhlings Gold', 'Fruhlingsmorgen', 'Golden Wings', 'Nevada' (pictured at top), 'Postillion', 'Red Mozart', 'Red Wand', 'Rosendorf', 'Sparrieshoop' (pictured right), 'Scarlet Fire' and 'Typhoon'.

Better Roses & Less Water

Sustainable gardening practices only start with smart and investigative plant selection. Preparing the growing site with good water retentive composted soil is a pre-requisite. After plant-out, the application of quality mulch, such as lucerne, pea straw, pine bark etc. is a must. In fact, anyone with a garden not practising a mulching regime is probably already living in a desert or near-desert of hydrophobic (water repellant) soil and dead or sad plants. Hydrophobic soils can be rewetted by products such as 'Saturaid' and 'Wetta-soil'. In a typical Aussie summer I apply liquid wetting agents at least twice.

In addition to soil preparation and mulches, if the disposition of your residence makes it logistically possible to channel grey water from your bathrooms to the garden, this would be a free, cost effective way of supplementing water.

Rain water catchment tanks and plant-sited, pressure compensated drip emitters are also good choices when it comes to smart water usage.

Oh! Bugger

Roses for all their value, beauty and attraction have many admirers including some bugs. My advice regarding dealing with these little suckers and blighters is to do so in an environmentally responsible manner. Within reason, we should live by the principles of Integrated Pest Management (IPM). IPM means learning to tolerate a certain level of aphids and caterpillars etc. in your garden, and not rushing off to the insecticide cupboard and then rushing out to nuke them as soon as one appears. A mindless 'ground zero' approach to pest control will only serve to kill or deter all the useful predators such as Lady Bird, Praying Mantis, Silver Eye etc. If you have the luxury of time aphids can be squashed by hand or blasted off by hose. There are even fine water jet wands available for this purpose.

If you have an infestation occurring then I would suggest spraying with a low-toxic Pyrethroid contact spray or one of the new generation synthetic sprays such as 'Confidor' which are systemic and one application will generally kill the whole cycle.

Caterpillars, Katydids and the like are best controlled by living by the old adage of actually taking the time to 'smell the roses' by going on garden patrol giving them the non-carcinogenic 'roll your own' treatment ie. between the thumb and fore-finger.

I'm Really Just a Fungi

There's nothing funny about a garden full of fungal disease and roses are one plant that can succumb to a decent dose of Black Spot or Powdery Mildew. The first rule of thumb in your prevention strategy is the previously-mentioned at least 50% sunshine per day rule. (Refer to our information pages on Black Spot of Rose and Powdery Mildew.

Next would be to use disease resistant cultivars similar to the ones previously mentioned. The third part of the equation would be to water your roses in the cool of the morning. I believe that the less stress your roses are under, the less susceptible they will be to disease. For example, if the day is going to be about 40°C it is far better to give your plants a drink and a cooler root run under the mulch prior to the heat rather than after, as they will be under less stress during night time and therefore able to cope better being a bit thirsty than during the heat of the day.

Secondly, by watering at night you would be creating the perfect micro-climate for fungal spores to propagate and race around the garden ie. damping down foliage and the garden environs in the cool of the evening. Bad enough when it rains at night, than you simulating this every time you water.

Conclusion

Many of the SGA principles I have applied to roses can also be applied to many other exotic cultivars together with a liberal application of common sense.

Grow Your Own... It's Good for the Planet

Marika Wagner, nursery staff member at Bulleen Art and Garden (an SGA certified garden centre) raises some important issues regarding fruit and vegetable growing, and the politics of growing in drought conditions.

To 'grow your own' fruit and vegetables is one of the most environmentally friendly things you can do and here's why!

1) Saves water. According to a study done by David Holmgren, co-founder of 'Permaculture', (Holmgren Design Services) efficient backyard growers can use as little as one fifth of the water compared to commercial growers per $ value of produce.

2) Saves up to 25% of greenhouse gases, by eliminating 'food miles'. This means our fruit and vegetables don't use excess energies, that is, they aren't being machine harvested, transported to sorting sheds, stored in cool rooms, transported to market, then to supermarket, lit up by fluorescent lights, and then transported again to homes to be then stored again in the fridge. Plus they lose vitality and freshness along the way.

3) Reduces the overall Australia wide use of biocides like herbicides, pesticides and fungicides. This is because home produce gardens are naturally quite biodiverse and of a small scale, therefore more resilient, and easy to apply natural pest control methods to.

4) Frees up agricultural land to revert back to natural systems which means more beauty for our children, our grandchildren, our tourists, our wildlife and us to enjoy. It means a chance for the planet to gain back forests, biodiversity, water catchments and salt free topsoil.

Growing your own is good for us too

- Home grown fruit and vegetables give us the best of nutrition by giving us access to fresh produce at our doorstep that still contains its maximum amount of vitamins and live enzymes.

- Everyone knows that the fresher the food, the higher the vitamin content, but enzymes are important too because they aid the body to assimilate foods properly without causing undue stress and premature aging on the body's own enzyme producing systems. How many people become sick unnecessarily because of poor digestion and malnutrition? Stomach cancer, bowel cancer, fatigue and feeling old before you're old? For us to gain the benefit of live enzymes, the food must be uncooked and less than 3 hours old, something you can only get from a local garden!

- Brings people and families together outdoors to gain healthy organic produce, fresh air, exercise and an awareness of our connection with nature. Get off that couch!

- Saves money. Not all of us can afford an organic grocery bill every week, but most of us can afford some packets of seed and a bag of organic fertiliser that will provide for months.

- Gives us something to be proud of, and not just for the reasons above but consider: Punnets of mixed herbs, tomatoes and basil, $14 Bag of organic fertiliser, $5 Serving your first, delicious, organic, home grown pasta sauce... priceless!

Feeding Birds in the Garden

Food for Thought

To feed birds or not to feed birds in the garden is an interesting debate. If you are going to put out feed to attract birds we ask you to consider the following information from the Bird Observers Club of Australia.

- Supplementary feeding increases the numbers of any single species in the garden, but does not necessarily increase the variety of different birds you will see.

- Planting a mixture of trees, shrubs and ground covers is more beneficial to birds than a bare lawn with one specimen tree and a feeding tray.

- Birds don’t need artificial nectar feeders – there are many nectar-bearing shrubs available.

- Artificial nectar feeders attract honeybees and wasps, can ferment in warm weather making birds ill, can be taken over by aggressive birds and can make birds ill and unhealthy if they only eat nectar and not a mix of food groups.

- Never provide so much food that the birds become dependent on it. If, for any reason, you are suddenly unable to feed them for a few days, some may die.

Wherever you live, feed only as much as will be eaten within half an hour and every now and again deliberately miss a day. Place birdbaths and feeding stations near a dense, perhaps prickly bush where the birds can quickly hide from predators such as cats and hawks.

Summarised from the Bird Observers Club of Australia with permission.

For more information visit http://birdlife.org.au/

Composting Big Time

Look what’s happening to our garden waste.

SGA visited the Epping Resource Recovery Facility in Victoria which was developed by Greenplanet and is now part of SITA. It’s turning our ‘green resource’ into quality mulch and compost – and it’s certified organic too. The finished product is shown here, still steaming hot!

‘Recycling is also about reusing!’ That was the word from Greenplanet’s sales manager Michael Rogers, seen here on the left with Greenplanet’s production manager Anthony Green. When the mulch made from your garden waste is this good, that’s enough reason to buy it back.

This SITA facility is recycling green waste from Whittlesea, and Whitehorse transfer stations and residents, and the Nillumbik kerbside collection and there are other similar facilities in most other states.

The amount of plastic bags and other non-compostable rubbish found in the kerbside green waste is very disappointing. The photograph here shows how important it is to keep rubbish out of green waste.

Greenplanet designed and built their own mulching machines. They developed a system of mulching to remove the rubbish, this means that 90% is recycled compared to only 30% in the past. The rest is rubbish that goes to landfill, as shown here.

Despite most of the rubbish being removed, kerbside waste will still have small, occasional particles of contaminants like plastic in the final compost, so this is blended with soil to create an organic soil blend.

Clean green waste that comes from waste transfer stations (the Tip in old-speak) doesn’t have the contaminants. It is this composted mulch product that is sold in bags or in bulk.

The Process

The green waste is mulched, then piled up in rows, called windrows.

The windrows are monitored stringently. They are turned regularly to keep the material aerated and to ensure that every bit of it is heated to more than 55 degrees for a sustained period of time. (This is required by the Australian Standards for composted mulches.) The high temperature kills weed seeds and pathogens – it’s pasteurization.

After a minimum of 21 days the pasteurized mulch is reground and passed through a screen to remove any large material (as seen here). The mulch is now ready to face the world – again!

Gardens love the addition of natural organic materials to improve soil quality and reduce evaporation. It also reduces the amount of insecticides and fungicides that you will need to use.

No chemical additives are used in the production of this mulch, so it complies with the highest standards and has the Compost Australia Leaf Mark.

Chemical Terms

Use this guide to help you make the most sustainable decision possible when, if there is no alternative, you need to use chemicals.

Active Ingredient: The portion of the chemical formulation directly responsible for herbicidal/pesticidal effects.

Biological Control: Using biological methods to control pests, eg. using the bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis to control caterpillars.

Broadcast Application: An application of spray over an entire area rather than only on individual plants.

Broadleaf Weeds: Plants with broad leaves, including flowers, trees, and many common weeds of lawns.

Certified Organic: Denotes products that have met strict guidelines set up by government approved certifying associations when grown, processed and handled.

Contact Herbicide: Only affects the part(s) of the plant(s) that the herbicide is applied to. When contact herbicides are applied to established perennial weeds, the above ground sprayed portion of the weed is usually destroyed, but regrowth can occur from the underground parts of the plant (The roots, rhizomes or tubers).

Dormant Spray: A spray that is applied after a deciduous plant has entered a stage of dormancy - that is, dropped its leaves (generally this occurs in winter).

Drift: Spray particles that are carried away from the target plant by the wind.

Foliar Treatment: Applying pesticides to the leaves (foliage) of the plant.

Integrated Pest Management: Using a combination of biological, chemical and/or mechanical means to control a pest.

Knockdown herbicides: May be either contact or translocated and can are used for the control of emergent and/or established weeds.

Leaching: The downward movement of the pesticide/herbicide into the soil, usually associated with water movement.

MSDS: Material Safety Data Sheet.

Mode of Action: The chemical reaction that takes place when a plant is treated and controlled by an herbicide.

Non-Selective Herbicide: Doesn't discriminate between target and non-target pests.

Noxious Weed: A plant that is required by state law to be controlled and eradicated.

Organic: Technically, any compound containing carbon, which is present in anything that has ever lived! When choosing organic products search for certified organic products to be on the safe side!

Pesticide: Substances intended to repel, kill, or control any species designated a "pest". This includes weeds, insects, rodents, fungi, bacteria and other organisms. This family of pesticides includes herbicides, insecticides, rodenticides, fungicides, and bactericides.

Post-Emergent Herbicide: A herbicide used to control plants after the plant emerges from the soil.

Pre-Emergent Herbicide: A herbicide used to control plants before the plant emerges from the soil.

Residual Herbicide: A herbicide placed on the target area that remains active in the soil for a period of time.

Selective Herbicide: Controls only certain types of plants without affecting other types of plants. Some of these act by interfering with the growth of the weed and they are often based on plant hormones.

Surfactant: Surface-active agents, emulsifiers, detergents, spreaders and dispersing agents capable of improving the effectiveness of the herbicide.

Systemic: A chemical which is absorbed directly into a plants vascular system. This method is used either to kill pests feeding on the plant or to kill the plant itself.

Culinary Herbs

Many culinary herbs are annual plants (or are treated as annuals in some regions), while others just keep on keeping on for years!

The best of the longer lived culinary herbs also serve other useful purposes in the garden, such as companion plants, pest repellent plants, hedging plants, or simply as attractive plants dotted through the garden.

Obviously the following is only a list of common favourites - there are many more to choose from. You may wish to refer to the references below for more information and inspiration.

Most herbs (except where noted below) require full sun and some can be quite drought tolerant once established (especially Rosemary, Sage and Thyme). And most can also be grown in containers.

What's more, they are the easiest of plants to grow and propagate! Most will strike readily from cuttings (which is the quickest way to propagate new plants) but also from seed.

Bay Tree (Laurus nobilis)

It is a tree and can grow to 12 metres in height, and although it can be a slow grower, in the right conditions it will grow pretty quickly. Consider confining to a pot or be prepared to regularly prune. It has a dense canopy so conditions are very shaded underneath and it also has a dense fibrous root system, which makes it difficult to grow plants underneath. Bay Tree can be pruned quite hard and it looks good as a standard. It is often used as a topiary specimen too (so if creating shapes is your thing, give this one a try).

Chives (Allium schoenoprasum)

Closely related to onions and garlic, chives grow in grassy clumps. Harvesting is simply a matter of chopping off a few leaves as required. Ideal for growing in pots as well as in the garden, chives are easily maintained and new plants can be started by dividing clumps or growing from seed. There is also a garlic flavoured species known as, you guessed it, garlic chives (Allium tuberosum)!

Marjoram (Origanum majorana) and Oregano (Origanum vulgare)

These two are so closely related and grow so similarly, we've lumped them together. Oregano has a sharper flavour than Marjoram. Both are spreading plants, more like groundcovers than clumping plants and both look fabulous spilling over walls, terraces, pots and the like. There is also a golden coloured Oregano.

Mint (Mentha spp.)

It can become a messy and invasive plant in the garden (as can be seen in the image here, where it's taken over an entire garden bed), so mint is best confined to a pot. It requires shade and a damp situation. Mint can be grown very easily from pieces of stem - in fact it's so vigorous the stems will sprout roots growing in a vase of water!

Parsley (Petroselinum crispum)

It can't possibly be true that you have to be wicked to grow parsley well, but that's the old saying! There are two commonly grown varieties of parsley - the common curled parsley and the stronger flavoured Italian parsley, with its flat leaf. Parsley is biennial, which means it will last a couple of years, but it is notorious for dropping dead or running to seed if conditions don't suit it. It doesn't tolerate dry conditions and has high nutrient requirements. It will grow in dappled shade as well as full sun.

Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis)

Rosemary is a great hedging plant, great pest repellent plant, and great companion plant for carrots especially. It can get woody and messy if not pruned regularly, and once it gets very woody, severe pruning can mean an end to it. It is best grown in full sun but will tolerate semi-shade. It can be easily propagated from cuttings, which strike very readily. Prostrate or low growing forms are available, and look out for specimens with the most vivid blue flowers (colour intensity can vary a lot).

Sage (Salvia officinalis)

In cooler climates Sage has a tendency to die back over winter, but it bounces right back in spring. It needs full sun and it is very drought tolerant once established. Sage is an attractive herb in the garden as it has silver grey leaves and produces tall spikes of violet flowers. Please note that there are other Salvia species that are purely ornamental.

Tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus)

This herb is more a spreading groundcover, although it can grow to 90cm tall. Its soft, dark green leaves look delightful weaving through the vegetable garden, and the licorice smell and flavour is even better. Tarragon needs full sunlight and in cooler climates it will die back during winter. It can be divided or grown readily from seed.

Thyme (Thymus vulgaris)

Thyme can vary a bit in appearance. Some plants clump and others are more like groundcovers. There are many varieties available including Lemon Thyme, which, as the name suggests, has a distinct lemon smell. Thyme is great in containers, as a garden border plant and for spilling over walls and terraces etc. It requires full sun and is quite drought tolerant once established.

One to avoid growing in your garden:

Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare)

Unfortunately fennel is a garden escapee of some importance and its escape is widespread, so this is one herb to buy as either seed or fresh leaves and plants. If you do have to grow it, don't let your plants set seed or try placing bags over the maturing seed heads to ensure you collect them and they aren't distributed far and wide. Florence fennel has a bulbous base which is cooked and eaten as a vegetable called finocchio.

Information sources:

Yates Garden Guide, 42nd Edition, 2006, published by Harper Collins Publishers.

Useful reference books:

Penny Woodward's Australian Herbal, published by Hyland House.

Woodward, P., Asian Herbs & Vegetables, published by Hyland House.

Jackie French's Household Herb Book, available from www.greenharvest.com.au

For design inspiration:

Bartley, J.R. 2006, Designing the New Kitchen Garden, published by Timber Press (but beware, this is a USA book, so specific plant information or plant species may not be appropriate - always check for local weediness too).

All pics © Elaine Shallue (SGA)

Leadbeater's Possum

Leadbeater's Possum - Adopt-a-nest box Project

Leadbeater's Possum (Gymnobelideus leadbeateri) is an endangered possum restricted to small pockets of remaining old growth mountain ash forests in the central highlands of Victoria, Australia north-east of Melbourne. Leadbeater's Possums can be moderately common within the very small areas they inhabit: their requirement for year-round food supplies and tree-holes to take refuge in during the day restricts them to mixed-age wet sclerophyll forest with a dense mid-story of Acacia. It is the only species in the Gymnobelideus genus. It was named after John Leadbeater the then taxidermist at the Museum of Victoria.[3] In 1971, the State of Victoria made Leadbeater's Possum its faunal emblem. (Information from Wikipedia)

In 2006, 'Project Possum' (the Australian Geographic Nest Box Project) commenced, bringing together a dedicated team of Leadbeater's Possum experts including scientists, representatives from State Government agencies and community groups. The aim of the project is to provide additional den sites for Leadbeater's Possums by installing nest boxes at strategic localities throughout their range. The goal of installing 200 nest boxes should provide dens for a significant proportion of the approximately 2,500 Leadbeater's Possums remaining in the wild.

In 2006, 'Project Possum' (the Australian Geographic Nest Box Project) commenced, bringing together a dedicated team of Leadbeater's Possum experts including scientists, representatives from State Government agencies and community groups. The aim of the project is to provide additional den sites for Leadbeater's Possums by installing nest boxes at strategic localities throughout their range. The goal of installing 200 nest boxes should provide dens for a significant proportion of the approximately 2,500 Leadbeater's Possums remaining in the wild.

For further information, download the pdf Adopt a nest box promo

Information sources:

Photographs are courtesy of Frederico Rossignoli (Fred the Snake Man), www.snakeshow.net

Nestboxes

Australia boasts an amazing and diverse range of native fauna, including our brightly coloured parrot species, our cheeky sugar gliders, our ever-present possums and our elusive micro-bats.

Australia boasts an amazing and diverse range of native fauna, including our brightly coloured parrot species, our cheeky sugar gliders, our ever-present possums and our elusive micro-bats.

All these animals, and many more, have two things in common:

- They all live in tree hollows

- They desperately need your help!

Due to the removal of native trees across Australia for building, logging, agricultural or firewood purposes, millions of natural tree hollows are lost every year. The devastation is particularly apparent in urban environments, where the loss of established trees has seen a dramatic decline in native fauna over the last fifty years due to a lack of appropriate habitat and nesting sites. Even if you live in an area with quite large trees, hollows usually take over 100 years to develop. Thus it may be many years before appropriate nesting / roosting sites are available for many species. It is this lack of habitat that places significant stress on our native animal populations, and can result in once common garden residents becoming rare or non-existent in our suburbs.

We can help!

It is possible for us to make a difference, right here in our own gardens!

Loss of habitat has had a massive impact on heaps of native animals. But, you can supplement and improve the resources available in your area by building your own nest box, or purchasing one made to specifications. This can provide a range of native birds and animals with shelter, and you with hours of joy watching once elusive fauna frolic in your backyard!

There are a few things you need to consider when installing a nest box (or two) in your patch.

Firstly: Check out with your local council what native birds and animals can be found in your area.

Secondly: Plant locally appropriate native plants nearby. Speak to staff at your local nursery or check out council resources regarding suitable plants for your area.

Thirdly: Provide water for any visitors, but NOT additional food sources. Our native friends love the additional water, but can become sick and dependant on humans if we feed them. Oh, and put the water source out of reach of any hungry domestic pets (especially cats!).

Lastly: Keep an eye on your cats and dogs; they can cause some real hassles for our native mates. Keep cats in at night and fit them with a bell or two. Cats can actually learn to stalk birds and other native animals without making their bell ring... so fitting multiple bells to your cat's collar is a handy idea. Keep adding bells until they can't walk without sounding like Santa Claus barrelling down a chimney.

Remember, wildlife nesting boxes come in loads of different sizes and shapes, many specific for one or two species, so it is important to do a bit of research before sticking one in the nearest tree. Most councils have comprehensive lists of locally native fauna that you can hope to attract back to your yard.

Microbats

Microbats

A number of species of these small, insectivorous bats can be found throughout Australia. Often referred to as the gardener's friend, microbats keep pest insects under control in the home garden. Bat nesting boxes are designed specifically for insectivorous bats, and are undesirable to other pest species (eg: Mynas, Bees), due to the entry located at the bottom of the box. It is also a good idea to affix some Hessian to the top of the inside of the box to enable the bats to cling to something while sleeping. Microbat roosting boxes should be located as high up in the tree as possible, and facing east to catch the morning sun.

Parrots

Parrots

No habitat garden is complete without the squawk and chatter of some beautiful locally native parrots, including the Musk Lorikeet, Rainbow Lorikeet (pictured here) and even the Yellow-Tailed Black Cockatoo. Parrot species feed on the nectar from Eucalypts, and require hollows in which to breed and roost. Unfortunately, parrot nesting boxes can also be attractive to some pest bird species, such as Mynas, Starlings and even feral Honeybees. In order to discourage these pests, it is advised by the Australian Bird Council that nest boxes be placed close together, to allow parrots to compete with both Mynas and Starlings. It is also recommended that a "baffle" be installed over the front of the nest box, allowing our clever parrots entry to the nest box while confusing pest species.

When situating the nest box, remember to provide as much protection from rain, wind and direct sun as possible. It has been found that facing parrot boxes in a south-east position is suitable. Also, remember that parrots will not provide their own nesting material, so placing suitable material in a box prior to hanging is advised. Decayed wood, shredded bark or untreated wood shavings are perfect for this purpose. Late winter to early spring is the best time to erect a parrot attracting box.

Brushtail Possums

Brushtail Possums

Alright, so not everyone loves this familiar Australian native due to their voracious appetites, taste for our exotic plants, and love of our rooves. But, the installation of a brushtail possum nest box my actually help you rid your house of these noisy natives! Possums are territorial, so to remove them from your roof you will need to block their access point. Do this in the evening AFTER they have left for their nightly rambles! Have a nest box installed away from the house as an alternative den, and once their access to the roof is blocked, they will take up residence there. Possum boxes should be placed at least three meters from the ground, and mounted so that they are leaning slightly forwards. This will assist their access into and out of the box, especially for young possums and will also help with drainage. Brushtail possums feed at night, mainly on leaves and fruits, and nest during the day.

Ringtail Possums

Ringtail Possums

Ringtail possums, although not as familiar as Brushtail possums, are common and an important element in locally native food webs. Ringtail possums will generally build their own nest (or "drey") from bark, leaves and grass, usually in dense undergrowth. They will occasionally utilise an appropriate nest box. Ringtail possum nest boxes have a smaller entry hole than brushtails, but should be mounted in the same fashion. Ringtail possums have developed a real taste for rose buds, so, if this species is sighted in your garden, covering your precious roses or using a possum deterrent may be necessary. Further information on protecting your property and ornamental plants from possums can be found on our factsheet Living With Possums... Without Going Nuts!

Sugar Gliders

Sugar Gliders

Perhaps one of our most well loved indigenous marsupials, the sugar glider, is rapidly disappearing from our urban areas due to habitat destruction. Sugar gliders are only found in areas where there are hollows for nesting and are generally seen amid tall eucalypts with adjacent wattle species for feeding... and they really do need our help. By installing a nest box in an established Eucalypt on your property, you could be assisting a group of five or more sugar gliders (these guys love to nest in groups). And you'll be doing your garden a favour too... research has shown that Eucalypt trees that have sugar gliders nesting in them are far healthier than those without gliders due to the amount of insects consumed by these hungry little locals. Sugar glider nest boxes have very small openings, which sugar gliders love... and pest species hate!

Kookaburras

Kookaburras

Perhaps the most iconic of all Australian birds, the Kookaburra is a welcome visitor in most suburban backyards. Feeding mainly on insects, worms and crustaceans, Kookaburras utilise hollows for breeding purposes, and the mounting of a nest box suitable for these cheerful natives will give them a helping hand in your community. Kookaburra nest boxes are horizontal in design, and need to have a small opening at the front through which young may excrete waste. Kookaburras can make fascinating studies in the suburban garden, due to their methods of hunting, their shared incubation duties, and the fact that they mate for life. Kookaburras will generally provide their own nesting material, and boxes should be mounted as high as possible in a protected position.

General Information On Nest Boxes

There's a pest in my box! What should I do?

The biggest concern faced by people erecting nest boxes is the occupation of these artificial hollows by introduced or pest species. These species include Common Mynas, Blackbirds, European Wasps, Honeybees and Sparrows. The occupation of hollows (both natural and artificial) by these pest species is a significant concern for the well-being of our locally native species, and boxes should be monitored routinely for signs of habitation by unwanted species. If a nest box is found to be occupied by a pest of some description, it is best to deter further occupation by removing any eggs and nesting material of the inhabitant, close off the nest box for a period of time, and assess the size of the entrance hole to the box.

Certain species prefer particular entrance holes sizes, and the correct size can help prevent unwanted visitors to the box (70mm prevents Brush-tailed Possums, 45mm prevents Common Mynas, 35-40mm prevents Starlings, 28mm prevents House Sparrows and 26mm prevents Tree Sparrows). The installation of a "baffle" at the front of the box (especially parrot boxes) is advised to discourage entry by pest species. Regular inspection of the box (weekly after placement) is recommended to avoid unwanted species moving in and displacing locally native wildlife. Honey Bees can be removed from a box by the placement of pest strips inside the box. It is recommended that this be performed at night time, while the bees are inactive. This will kill the bees, and they will subsequently require removal.

To feed or not to feed... that is the question!

Rightio, so this question gets asked time and time again, and there are conflicting schools of thought regarding whether or not people should feed our indigenous fauna. The short answer is NO! Feeding of native fauna is not advised for the following reasons:

- Native fauna can become dependant on food provided by humans, causing them to forget how to hunt and source food for themselves. This can become a real issue when humans move house or go away on holidays, as the "reliable" food source has disappeared. Many native birds and animals used to this repeated feeding will perish in these situations.

- Human food, and even products marketed as suitable for feeding to wildlife often contains dangerous additives, chemicals and preservatives that are harmful to native fauna, and can cause sickness, adverse reactions and even death.

- Repeated feeding of many animals can alter natural behaviours, causing normally passive birds and animals to become highly aggressive, towards each other and towards humans. This is evident in many campgrounds and urban areas, where generally shy wildlife have become aggressive to the point of threatening and injuring humans in their search for food.

- Location of feeding areas within the nesting territory of many birds and animals disrupts their nesting activity, as nest guardians are busy defending their territory from other species encouraged by the food source.

What about water?

Water is recommended, as long as it is out of reach of predators, such as domestic cats and dogs. An available water source will almost guarantee the arrival of a number of bird species, particularly parrots.

<h3 >What sort of plants will encourage wildlife?

>What sort of plants will encourage wildlife?

Generally, it is recommended that indigenous plants be chosen for the creation of habitat in your garden. Indigenous (or locally native) plants are those which were, prior to European settlement, common to the area. Locally native plant species are often also present in areas of remnant vegetation that may exist in our communities. By selecting appropriate plant species, you are re-establishing lost habitat, in turn making your community a more desirable place for locally native birds, animals and insects to live. For information of plants indigenous to your area, contact your local council or helpful nursery person for a list of plant species to suit every situation.

How long until someone moves in?

Don't be surprised if it takes some time for native fauna to occupy your nest box. With the exception of Rosellas (who are inclined to move in straight away), most indigenous fauna species like to "suss out" a hollow before setting up house, so don't be too upset if it takes a little while!

A locally native animal has moved in! What do I do now?

First and foremost... congratulations. You are helping re-establish habitat for native species that have been displaced by humans and introduced pest species! Now you have to keep them there, and make sure their stay is as comfortable as possible. Avoid the temptation to open the box and look at the inhabitants. This is extremely threatening to our native fauna, especially if they are nesting, and may cause the bird or animal to leave the nest box. A great way to monitor behaviour is to view the inhabitants from a respectful distance, and record their movements. This can be a fascinating endeavour, and information gathered in this manner is often utilised by councils and community groups.

How do I mount my new nest box?

How do I mount my new nest box?

Generally, the majority of species prefer a box with a north-east to south-east aspect. This allows some warmth from the morning sun, while avoiding direct sun in the middle of the day. Nest boxes should be located so as to minimise impact from weather, such a rain, wind, and harsh sunlight. Boxes should be placed as high as possible. This avoids vandalism and disturbance from humans, and minimises the risk posed by domestic and feral animals, such as dogs and cats.

To mount the nest box to a suitable tree, it is recommended that the rear of the box be attached to the tree with galvanised self drilling screws (Type 17 - 14G x 100mm long Hex Head or Bugle Head Batten Screw). This minimises the risk of injury to the tree, and is preferable to straps, wires or chains, which can cause damage to the tree as it grows. Galvanised self drilling screws are also more secure, and provide greater stability, making the environment more comfortable for the inhabitants. If possible, the box should be angled slightly forwards, as this allows young to exit the box more readily. It also aids drainage, keeping the nesting box cleaner and inhabitants happier. If the nest box is removed from the tree, don't forget to remove the screws.

Can I use a fallen log as a nest box?

NO! Although this ready made roost may seem the ideal nesting box, by removing this log from the ground you could be destroying valuable habitat for some amazing ground dwelling indigenous animals. Skinks, insects, frogs and even some locally native birds and mammals rely on fallen timber for shelter, food and protection, and it is for this reason that fallen timber should be left on the ground.

Bees (Good & Bad)

Are there bad bees? You bet.

Since arriving in Australia about ten years ago, the bumblebee (Large Earth Bumblebee - Bombus terrestris) from North America and the UK has quickly spread across Tasmania, where it's out-competing other species.

Now scientists say it's probably only a matter of time before the bumblebee arrives on the mainland, with dire consequences.

‘Environmentally they're as potentially damaging as some of the more familiar animals like cane toads,’ explains entomologist Dr Peter McQuillan from the University of Tasmania, in an interview on ABC Radio National’s PM program.

These bees are large, hairy and live in very large social groups. No native bees resemble them.

The bumblebee’s pollination technique sets it apart from the honeybee. The bumblebee ‘buzz pollinates’, which means, it holds the plant and ‘buzzes its wing muscles’ to shake all the pollen out. Buzz pollination is known to advantage many weedy species, including Scotch Broom) and Deadly Nightshade. And this is one of the potential environmental problems.

Bumblebees also compete with birds and animals for nest sites. In Tasmania, the swift parrot is already rare and now the bumblebee is outcompeting it for nesting sites.

These bees are aggressive stingers when guarding their nest and, unlike the honeybee, they can sting repeatedly. This of course makes them a threat to humans as well, particularly people who are allergic to honeybee stings.

Research is currently being undertaken in Tasmania to assess their effect on the environment and their spread.

If you suspect you have collected a bumblebee, send the insect for evaluation. Complete the following steps and remember, they sting – repeatedly:

* Kill the bee in methylated spirits or ethyl alcohol

* Place in a tightly capped plastic tube or jar (not an envelope)

* Label the container with your name, address, telephone number and the date, time and exact location where the insect was collected. If possible, include other relevant information such as habitat, host plant or flower, and the weather conditions.

In Victoria, post to DPI Crop Health Services, Private Bag 15, South Eastern Mail Centre, 3176. Other States, please contact your relevant government body.

Good Bees

On a brighter note, native bees are proving their worth as honey producers and as superior pollinators to the European honey bee.

In an ABC Radio National interview (PM), CSIRO entomologist and beekeeper Tim Heard expounded the virtues of stingless natives bees. European honey bee populations have been ravaged by a parasite called veroa mite and he believes it’s only a matter of time before it reaches Australia. Australian native bees could be ‘an important insurance policy for the horticulture industry’.

Some native bee species are already being used to pollinate crops. For example, in the Northern Rivers region of NSW Trigona carbonaria (a species of stingless native bee) is being used very successfully to pollinate crops like macadamias, avocadoes, melons, strawberries, and apples.

Honey bees are incidental pollinators, with their main role being the collection of nectar. Australian native bees are active pollinators and their main role is the collection and transfer of pollen. What’s more, the native bees are a lot easier to handle because many are stingless!

The honey from native bees, which has a unique tangy flavour, is known as Sugarbag. The honey’s potential medicinal properties are also raising interest.

Will Archer, of Stingless Bees, has researched and experimented with breeding stingless native bees in Coff’s Harbour, NSW. He has designed a beehive to suit native bees. It's taken him nearly three years to perfect the design, with the latest version being a round hive made of PVC and lined with polystyrene.

“It’s difficult to extract honey from native bee hives without damaging the hive, but I've designed a hive that's so simple all you need is a spoon basically," he says. It will be another couple of years before Will Archer has bred enough bees to produce honey for sale. He also aims to sell the hives for crop pollination. Will already has over 200 people on the waiting list for his Sugarbag!

There are about 2000 species of native bee, many of which are solitary (as opposed to the hive-forming type), so if you would like to know which ones you have in your area, or information on building and maintaining hives, visit the website: www.aussiebee.com.au

Attracting native bees to your garden is quite simple. They like eucalypts, grevilleas, callistemons and melaleucas, amongst many others, and they also like non-native plants like roses.

A helpful strategy is to increase habitat, like creating nest sites for solitary bee species by drilling holes in pieces of hardwood timber.

All photographs courtesy of Australian Native Bee Research Centre, North Richmond, NSW.

Spiders

Arachnids are not categorised as insects mainly because they have eight legs instead of six (although mites do have a six-legged stage during their development). Most spiders are beneficial in the garden but some mites aren't.

Spiders

As with any beneficial critter, the message is to encourage them.

Don't rip down webs for a start and don't disturb spider egg cases. Egg cases are usually white, fuzzy balls of various sizes, depending on the spider species. Egg cases of Huntsman Spiders, for example, are marble-sized.

Incidentally, Australian Huntsman spiders are a diverse and relatively harmless group of spiders, with 13 genera and 94 described species. They are one of the most beneficial garden spiders, plus it's good luck to have them in your house - at least that's what my mother assures me!

Female Huntsman are protective of their eggsac (shown here) and will stand guard over it, without eating, for about three weeks until the spiderlings emerge. She will then stay with her brood for several weeks.

Huntsman spider bites usually result only in transient local pain and swelling. However, some Badge Huntsman spider bites have caused prolonged pain, inflammation, headache, vomiting and irregular pulse rate.

To encourage spiders minimise the use of insecticides and miticides. Heavily vegetated areas or hollow structures are good habitat for spiders. However, the most important thing gardeners can do to encourage them is not to kill them!

Spiders hatch as miniatures of their parents and grow by gradually molting their exoskeleton.

For home gardeners, avoiding spiders is often their goal. The solution is simple - wear gloves when gardening!

Gardens for Wildlife

Attracting native animals to your garden can add extra colour and interest. It can assist pest control by attracting insect predators and can also contribute to keeping animal populations viable by providing a pathway for them to commute between bushland areas. All you have to do is provide your garden visitors with food, water and shelter.

The features of a good wildlife garden:

A variety of fruit, seed and nectar plants including:

- Flowering trees that are native to your local area.

- Dense and prickly shrubs for bird shelter.

- Local nectar plants for butterflies.

- Local daisy species for caterpillars.

Other elements such as:

- Mulched area for worms and beetle habitat.

- Water in a pond or birdbath.

- A sunny spot with a rock surface for lizards.

- Mature trees with hollows for nesting or install nesting boxes.

Other wildlife friendly practices:

- Reducing the use of pesticides in the garden will provide birds and small bats with a safe food source.

- Securing cats and dogs, especially at night, so they don’t prey on native animals.

For more information visit http://birdlife.org.au/all-about-birds/birds-in-backyards/

Queensland Fruit Fly

Queensland Fruit Fly

(Bactrocera tryoni)

Queensland Fruit Fly was found in metropolitan Melbourne in January 2008. This is a matter of very great concern. Queensland Fruit Fly is a very serious pest of great economic significance because of the damage caused to the fruit industry. It may affect the home gardener who grows fruit and vegetables as well as the horticulture industries.

Plant Health Australia (PHA) is currently facilitating a major national initiative to improve the management and eradication of fruit fly. Those who live in an infected area should do all they can to eliminate this pest. This means caring for your fruit trees and disposing of all fruit correctly.

Inspect Regularly

Home grown fruit should be inspected on a regular basis for the presence of fruit fly larvae. The larvae may be easier to find than the adult fruit fly.

The adult fruit fly has a wasp like appearance. It is about 7 mm long. It is a reddish brown colour with yellow oval markings. The female fly lays eggs in the ripening fruit and the larvae burrows inside the fruit and so destroys it.

Most fruits can be affected including peaches, oranges, apples, pears, tomatoes and capsicums. There are traps which can be used to detect the presence of fruit fly. Some fruit, such as banana and avocado may be picked in a mature green condition, before fruit fly can lay its eggs in the fruit.

Control

If you grow any fruit trees they should be pruned regularly to a height that the fruit can be picked. Ripe fruit should be removed from the tree before it falls to the ground. Any fruit which does fall to the ground should be collected immediately and sealed in a plastic bag. The sealed bag should be left in the sun for 3-7 days so that the heat will kill the larvae and prevent them developing into fruit fly adults.

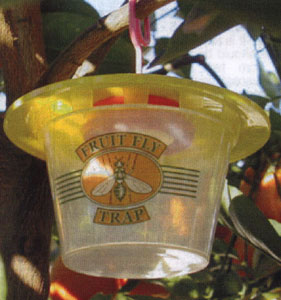

There are chemicals which can be used to prevent infestations or control fruit fly but there are also other methods, such as traps which attract the flies with a pheromone and then kill them with an insecticide.

Chooks to the Rescue!

Poultry are an enormous help in fruit fly control. If you design your orchard to incorporate chooks they will reward you by turning rotten fruit into eggs and happily spend hours scratching beneath trees looking for fruit fly pupae. Adult fruit flies are trapped on the ground for up to 24 hours after emerging from the pupae as it takes this long for their wings to harden. During this time the adult flies are also vulnerable to a roving chook. Where it isn't possible to allow chooks free range, small demountable fences can be used under trees vulnerable to attack by fruit fly.

If you find maggots they need to be accurately identified so that a method of eradication can be established. Contact your local Department of Primary Industry if you find maggots.

Exclusion Zones

Major fruit production areas such as the Sunraysia and the Riverland are in an area known as the Fruit Fly Exclusion Zone. This area was established to facilitate exports of their produce to both other areas of Australia and overseas. There are roadside bins for travellers to deposit any fruit before entering these areas. There is fruit fly in eastern Victoria and fruit may not be removed from this area.

Host Plant

Clivia sp. have been found to be a host for fruit fly. Fruit fly lay maggots in the developing fruit, so spent flower heads should be removed.

Interestingly, horticulture students doing research accidentally discovered this connection!

Contacts for State Government Departments:

Victoria 136 186, or free call 1800 084 881

NSW www.dpi.nsw.gov.au

Queensland www.qld gov.au, 132 523

SA www.pir.sa.gov.au/biosecurity/plant_health, 1300 666 010

WA www.agric.wa.gov.au

Image sources::

Top image courtesy of Rural City of Wangaratta

Second image courtesy of Department of Agriculture & Food WA

Trap image courtesy of www.greenharvest.com.au

Banner image: James Niland - Flickr: Queensland Fruit Fly - Bactrocera tryoni, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14743812

European & English Wasps

(Vespula germanica and Vespula vulgaris)

These closely related wasps are the scourge of Australian gardeners and barbecuers alike, with the ability to inflict mighty painful stings repeatedly and a nasty temper to match.

The European wasp was originally from Europe, North Africa and temperate Asia, but it has now spread to North America, New Zealand, South Africa, and South America. It was first discovered in Sydney in 1954 when hibernating queens were found in a timber consignment from New Zealand.

It wasn't until 1959 that nests were discovered in Hobart, then Sydney in 1975, Western Australia and Victoria in 1977 and then South Australia in 1978.

The English wasp first showed up Malvern, Victoria in 1958 and the nest was destroyed. Unfortunately more nests were found in 1960. Their distribution seems to be more restricted than that of the European wasp, but there isn't much information on their spread. They are found in Victoria and southeastern Tasmania.

Life Cycle

Queens of both species spend the winter hibernating and emerge in spring to look for nesting sites. Nests are usually built underground, in holes dug in the soil, but as we know, they can be found anywhere there is protection from rain and moisture and warmth, such as inside cavity walls, woodstacks, tree trunks and even inside pots.

The first batch of eggs laid are laid in a cluster of hexagonal cells made by the queen.

The first batch of eggs laid are laid in a cluster of hexagonal cells made by the queen.

Wasps make a type of paper by chewing wood fibre into a pulp. This is used as a protective layer over the cells, and on the outer covering of nests, which is cardboard like (as seen in the photograph here, courtesy of J.P.Spradbery, CSIRO Entomology).

These first wasps are workers (sterile females) and take over the nest building work of the queen, leaving her to dedicate her time to egg-laying. The nest will be enlarged continually through summer and autumn.

These first wasps are workers (sterile females) and take over the nest building work of the queen, leaving her to dedicate her time to egg-laying. The nest will be enlarged continually through summer and autumn.

Each worker only lives several weeks, but there could be thousands present in a nest at any given time during summer and autumn.

Their defence of their nest is legendary. They are vicious. Vibration, rather than sound, alerts workers to an intruder, who come swarming out to attack. Once a victim is attacked, chemical cues guide more wasps to the attack.

Foraging by workers occurs within 50 to 250 metres of a nest. And they will collect just about anything that is carbohydrate or protein, including fruit, insects, and carrion. This is taken back to feed the larvae.

Towards the end of autumn the workers build larger larvae cells. These will host the next generation of several hundred queens and drones (fertile males).

During autumn the queens and drones indulge in mating flights, with the queens then seeking out winter sheltering sites. The males die off, as do the remaining nest occupants, although there are situations where enough food and warmth has ensured survival over winter. The next season these wasp nests have the ability to become absolutely enormous.

Chemical Control

We've all heard enough wasp stinging horror stories to know that this is one insect to treat seriously and carefully.

Chemical control of this wasp is very efficient but it needs to be carried out in a safety conscious manner.

The Museum of Victoria provides the following rules for the 'Do It Yourself European Wasp Pest Exterminator'.

- Always treat the nest at night when wasp activity is low.

- Always cover your torch with red cellophane as insects cannot see red light.

- If possible, position the torch some distance from yourself, yet still illuminating the area to the treated.

- Always wear loose clothing, fully covering your body, a floppy hat or veil and gloves.

- Tell someone what you are doing and where you will be.

Above ground visible nests can be soaked with the spray of any commercially available insecticide.

Nests in concealed, confined or restricted areas can be destroyed with a pest strip. Considering that up to 20% of wasp nests in Australia occur in roof spaces and wall cavities, this is a good solution. Simply place the pest strip near the nest. In a wall cavity, cut up the pest strip and pass it through outside air vents near the nest.

Nests in concealed, confined or restricted areas can be destroyed with a pest strip. Considering that up to 20% of wasp nests in Australia occur in roof spaces and wall cavities, this is a good solution. Simply place the pest strip near the nest. In a wall cavity, cut up the pest strip and pass it through outside air vents near the nest.

These areas can also be soaked with spray from an insecticide surface spray or the area liberally sprinkled with insecticide dust.

In ground nests can also be treated with dust. Do not apply if rain is likely within 24 hours.

In ground nests will require two applications several days apart to destroy.

Chemical baiting has been trialled in vineyards in the Yarra Valley and Mornington Peninsula areas of Victoria, with considerable success. Minced meat was laced with the insecticide. It was found quite effective in reducing wasp numbers in areas where it was very difficult to locate nests.

In these trials it was noted that even when wasp nests are totally destroyed by this manner, new wasps will move into the area.

Obviously extreme caution must be taken with this option, as pets could also eat the meat.

Other control methods

Sticky traps can be used to trap wasps and in Britain net traps are used to prevent wasps entering factories. Wasps are also attracted to ultraviolet light and electric traps.

There are a variety of traps that allow entry but the wasp can't exit. The success of these traps depends on the attractiveness of the bait.

There are a variety of traps that allow entry but the wasp can't exit. The success of these traps depends on the attractiveness of the bait.

Sanitation (ensuring garbage is in containers with fitted lids for example, and removing food scraps as soon as possible), and proofing buildings against queens seeking nesting sites are also ways to reduce wasp activity.

Unfortunately, according to the researchers in this area, these wasps are here to stay. Total eradication is no longer an option. One upside is that despite their stinging ability, no deaths have been attributed to European or English wasps in Australia.

Information sources:

Kerruish, R.M. & Unger, P.W., 2003, 3rd Edition, Plant Protection 1, published by RootRot Press, ACT.

Museum Victoria

CSIRO

Banner image: Alvesgaspar [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

What are Pesticides?

Pesticides include insecticides, herbicides and fungicides, which are designed to kill insects, weeds and diseases respectively. Using pesticides may be necessary at times, but in many cases there are alternatives that are often more effective in the long run and less harmful to you and the environment.

Pesticides in the environment

What happens to pesticides released into the environment is not always known. They are either broken down or degraded by sunlight, water, other chemicals or microorganisms such as bacteria or remain unchanged in the environment for long periods of time. Some pesticides are selective against a given pest, while others are relatively non-selective towards a large group of organisms. After applying them to plants, pesticides can eventually end up in other parts of the environment, such as water, soil or air where they may affect other organisms.

Pesticides in our waterways

If a pesticide is very soluble it is easily transported by rainwater as runoff. Water from rain carries pesticides from lawns and gardens into nearby street drains. Street drains feed directly into waterways. Once in the water, pesticides dissolve, dilute or combine with other chemicals to create harmful combinations that can kill fish, frogs and aquatic life, limit beneficial plants and animals and increase growth of algae. Excess algal growth causes light deficiencies for plants and depletes oxygen levels that fish need to survive. Clean water is an essential part of our quality of life. We can help protect our rivers, streams, lakes and bays by rethinking and reducing our use of pesticides.

Pesticides in the air

Pesticides that are more volatile have the ability to evaporate and be absorbed into the atmosphere potentially moving long distances. Fine mists of pesticides can drift to nearby plants and kill them. Bees and other pollinators can be killed if a pesticide is sprayed when they are in the field. Pesticide sprays can also kill the natural enemies of pest insects. In the United States EPA studies on animals have shown that of the 34 chemicals that make up 95% of lawn pesticides, 10 are carcinogenic, 12 cause birth defects, 20 are neurotoxic, 7 alter the reproductive process, 13 cause liver damage, and 29 are irritants.

Pesticides in the soil

Pesticides that percolate through the soil may inadvertently kill beneficial organisms such as earthworms. They may also enter the groundwater and potentially pollute our drinking water. Pesticides are made to be toxic. These chemicals may affect your health, the health of your neighbours and the health of smaller animals and plants in your community. Be an informed consumer and use environmental common sense when using pesticides in your home and garden.

As a member of Sustainable Gardening Australia we ask you to consider chemical alternatives or use low environmental impact chemicals, slow release fertilisers and use only the amount recommended by the manufacturer. Try not to apply these chemicals before rain or on windy days.